De-Grossing, What Is It?

With lots of chatter about "unwinds" & "de-grossing" over the last couple of weeks and Jefco PB comments of the worst HF unwind in decades in December circulating on Twitter, I thought it might be a useful exercise to try to break the concept of de-grossing down a bit for those who don't fully understand the concept.

If you're like me, I was afraid to ask questions for fear of seeming stupid (to be clear, there ARE stupid questions at a hedge fund). So ask the stupid questions here.

WHAT IS GROSS?

Think of gross exposure as simply your "buying power". Many if not most hedge fund strategies are, on an unlevered basis, less risky than simply buying the S&P 500. A typical long/short market neutral portfolio is likely in the range of 2-4% annualized volatility (vs mid to high teens for the S&P 500). Given this low volatility strategy, it is logical and prudent to apply leverage to this strategy. Said differently, no investor would invest in a 3% unlevered return strategy as the risk-free rate differential is a non-starter. You can use the analogy of real estate investing which tends to drive boring returns outside of the use of leverage.

In this simple example, I take a 2.5% return on gross and through the accelerating impact of leverage turn that into a 12.5% return on equity.

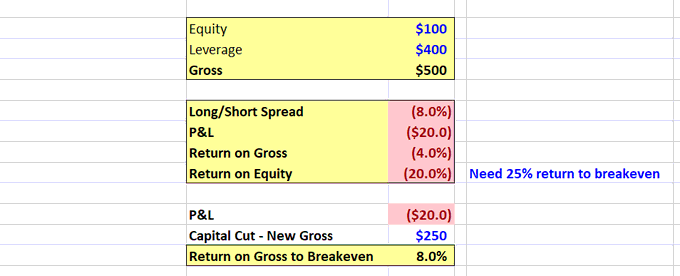

Leverage, however, can cut both ways (as any seasoned real estate investor can attest). If I go through a tough period of performance, call it 4% hit on gross. That 4% SEEMS like a small hit, but that flows through to equity at a multiplier given the leverage. All of a sudden, I am sitting on a 20% hit to equity.

Contextually, when people talk about drawdown limits of 2-5% at multi-manager complexes, one must consider the leverage. 2-5% SEEMS small for a beta-long investor, but the wrapper is different, and we ultimately care about preserving and growing investor equity. Given the leverage inherent in the business model, cutting left tails is a critical risk function. If I let returns on gross expand to the HSD/LDD across my PMs, all of a sudden I have major equity/margin call issues.

MATH OF DIGGING A HOLE

Given these leverage dynamics, both firm risk management and individual PMs (particularly at pods) are very focused, paranoid even, on preventing capital loss.

As a simple reminder, a 20% hair-cut requires 25% returns to breakeven. A 50% hair-cut requires 100% returns to breakeven. When you dig a whole, it's damn hard to get out of it (take it from a guy who has dug some holes in his life...).

And it can get even more challenging for volatility-budgeted, draw-down targeted capital. If I have a 4% draw on gross AND get my capital cut in half, I now need 8% return just to get back to even (which generally is 2-3 years of grinding P&L or 2-3 Sharpes of return).

FWIW, as a PM this was the most challenging dynamic I faced in markets. I was an ok PM, and could go on runs of strong P&L generation. But TOO OFTEN, I felt like 6 months of work was washed out in 6 days of unwind. And "good risk management" meant de-grossing and inoculating the book from further drawdown, effectively locking on those kerfuffle losses. Oh man, that sucked bad. A truly Sisyphean endeavor...

RISK MANAGEMENT

Given hedge funds deal with the rattle-snake of leverage, intelligent risk management is key. Many firms operate with a ruthless, programmatic drawdown target. Down ~2%, we take half your capital. Down 4%, we take all your capital. Seems cold? It is, but being "nice" with PMs who are running leveraged capital and may be on tilt starts to introduce existential risk into your entire equity base.

Risk management frameworks broadly are borne from academic finance of the 1970s and lean heavily on bell-curve distribution and factor-based risk models. Capital is largely allocated on a volatility or value-at-risk (VAR) approach which implies bell-curve distributions. We can all joke about the silliness of the bell-curve and how common 10x+ and even 20x+ sigma events seem to happen in markets (i.e. "this shouldn't happen in 17 trillion years"), so please understand the imperfections of academic risk models (and perhaps read Benoit Mandelbrot). Also, a study of LTCM and the failings of the academic lens of finance is also required for any self-respecting market participant.

The firms obviously know this as well, and a broad standard has been adopted in the hedge fund industry that "gross is risk". What does that mean? Effectively, we will calibrate the risk of my portfolio by running more vol/gross or less vol/gross and shift that pro-cyclically with the broader environment.

This view that "gross is risk" has helped to codify the iron law of pro-cyclical gross: when things are going well (i.e. L/S spread momentum) the hedge fund complex will gross up, when things are going poorly (i.e. L/S spread unwind) the hedge fund complex will gross down.

The iron law is a momentum rather than mean-reverting approach to spread & alpha capture. As a 15+ year participant and observer of the HF industry, this took me a long time to understand. "If the opportunity set is better, we should be grossing UP not DOWN". I thought the iron law was stupid (what I now call the "rage against the machine" approach). I still kinda do, and think being able to gross in a counter-cyclical mean-reverting fashion is a huge advantage in managing capital (Paul Enright did a fantastic podcast articulating this). But as I've matured and fully respected the impact of leverage, the iron law makes more sense to me. And pragmatically, if you are down 20-40% on equity, that doesn't necessarily put you in a strong position to lean into opportunities (at that point you may be fighting to keep capital and talent).

So I observe a confluence of,

The iron law of pro-cyclical gross holding broadly and building in intensity,

The trend of more capital becoming volatility budgeted (such that a step up in volatility will force a step down in gross),

Both individual PMs and firm risk managements are so keyed in on crowding & de-grossing risk that the push to "panic early" is a creeping endeavor. To me, these issues conspire to create a more jagged, violent market that can be very hard to comprehend on any given day. But hey, the market is the market. Our job as investors is to understand it and seek the opportunity within it.

ENTER DE-GROSSING

So if taking a 4% hit on de-gross to the face which will cause my capital to get cut and require 8% return on gross to breakeven is a bad way to run capital, what is a better way?

The storms will come. De-grossing and unwinds are now a permanent fixture of markets, at least for now.

Running a perfectly contrarian book isn't the answer. The average pod book makes 20-40bps per month...flipping that is effectively paying an insurance premium for a storm that may or may not come.

The most common method is the "early panic" system. If I see my book acting weird for 2-3 days, I will start to de-gross. Take capital off PROACTIVELY before I dig too big a hole. Make some portfolio nips and tucks to inoculate against the carnage as much as possible. If done well, perhaps I can turn what would have been a 4% hit to gross into a 2% hit to gross, maintain my capital, and be on my front foot to play the re-wind, mean-reversion of these blown-out spreads.

Maybe cut my gross down by 10-20%. That might be done by taking a few individual ideas down or might be an across-the-board cut. Gross is a risk, and when it appears a storm is coming, I want to batten down the hatches. Disagree with that method of running capital, but that mentality is the dominant force in markets right now. (The paranoia and total commitment required to steer a portfolio is a discussion for another day).

The real risk comes in the tape when we have so many PMs running so much capital that the "panic early" approach actually starts an avalanche of liquidity air pockets.

There are some practical methods of tail risk hedging and other portfolio approaches that I have been exploring in more detail to stay anti-fragile about the inevitable bullwhip of gross movements, mostly with single manager clients trying to adapt to these changes in price discovery. As those ideas mature, I will be sharing more here (some will stay proprietary).

There are also ways to evaluate crowding, positioning, and broader gross trends. The PBs have good (if not contradicting data, at times) that are anonymized. 13Fs generally are going to be too lagged (they worked in a Tiger world, not in a Pod world). That leaves us with surveying work and work on the price signals of individual securities.

Hope this was helpful and as always, happy to engage with any market participants who are on the leading edge of this trend (managers, PBs, reporters, etc)